80 years ago, Britain’s phony war with Germany was over and the nation, having endured the evacuation from Dunkirk, was bracing itself for heavy attacks from the air.

On the declaration of war in September the previous year, many golf clubs were required to do their bit. Suitable courses gave up land to agriculture, while key seaside locations had to be prepared as defensive positions. Hoylake was one of the latter.

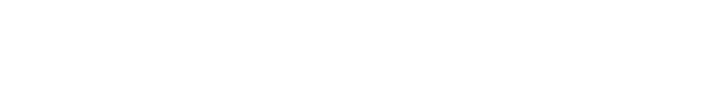

In 1947, as Royal Liverpool prepared to host The Open, Secretary Guy Farrar reflected on Royal Liverpool’s war years, beginning in mid-1939 when freedom’s lamps were burning but dimly and a shadow had fallen over that year’s Amateur Championship at Hoylake.

When the crowds dispersed, a friend of mine, a well known competitor, said to me, “When will the next Amateur be played, and how many of us here today will take part in it? The wonderful condition of these greens and fairways, and the care and labour of maintaining them, may seem of little moment in the near future.”

Guy Farrar

Farrar’s friend was right, and very soon men’s thoughts turned to more serious games than golf. The phony war was over. The real one had begun.

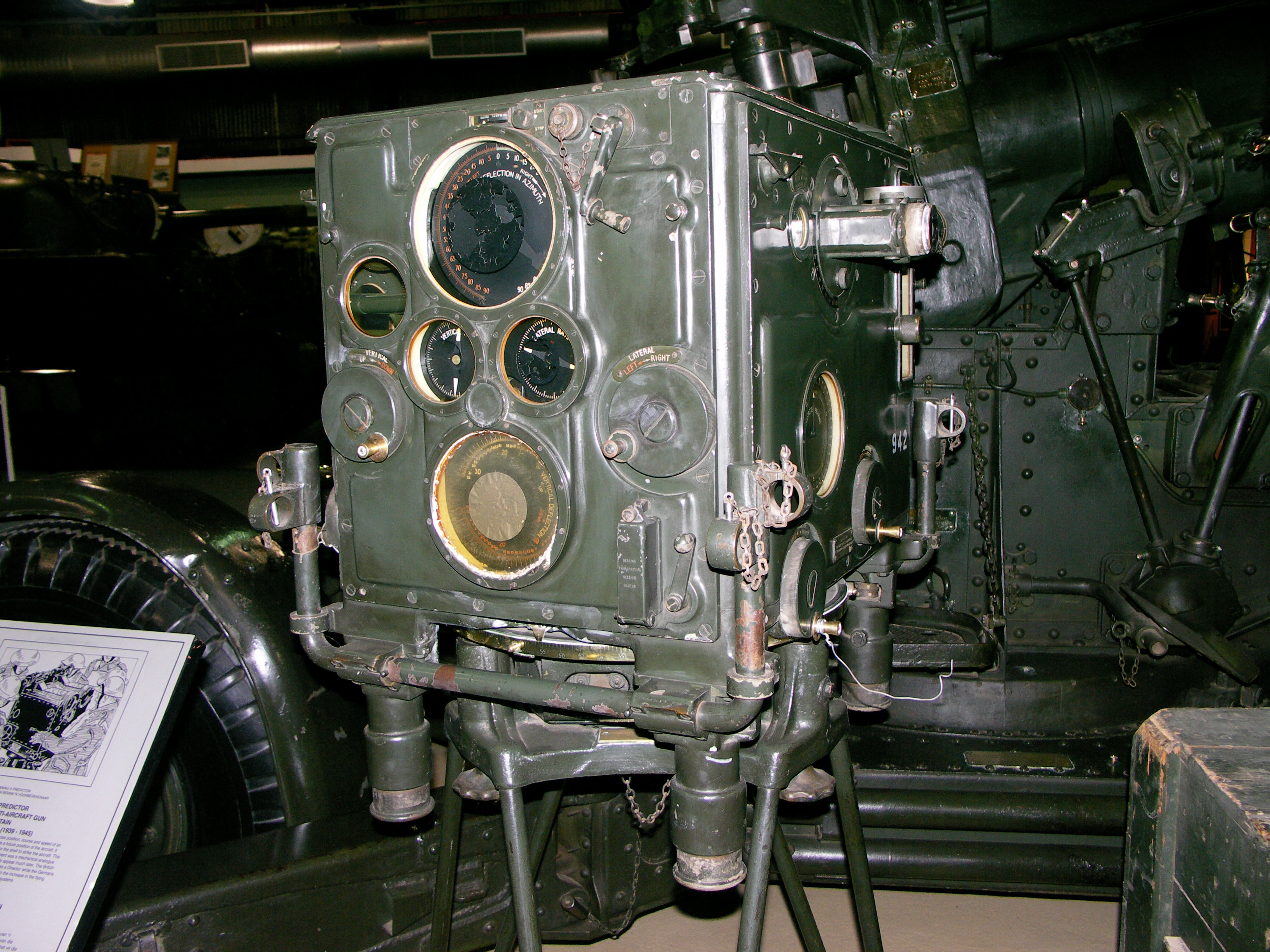

The first signs of war on the Royal Liverpool links were the arrival of a strange looking instrument, a predictor, said to be able to foretell the line of approach of hostile aircraft; certain elderly gentlemen beginning the task of digging trenches on various parts of the links, their leisurely and inexpert methods causing great amusement to the Royal Liverpool greenkeeper; a local contractor building a series of comic opera forts among the sand-hills; the dazzling beam of a searchlight, operated from a site near the Royal (17th) green, sweeping the night sky; the first German plane overhead; and the feeling that the long drawn suspense was over at last.

An anti-aircraft predictor

The enemy was soon identified, but turned out to be an unexpected one.

An invasion followed, not by German storm troopers but by sheep, a destructive army of occupation remaining in undisturbed possession of the links until the Spring of 1945. During the months following the fall of France, a chain of minefields laid on the landward side of the sand-hills was surrounded by over three miles of barbed wire after sundry sheep and dogs had come to a sudden end, and, on one occasion, two small children had been rescued just as they were about to wander amongst the mines. This wire isolated the Dee, Alps and Hilbre holes, so temporary ones had to be brought into play, but the proper greens were mown at intervals, thus preventing their complete destruction by prolonged neglect.

Guy Farrar's Nemesis

Guy Farrar's Nemesis

Things got worse before they got better, and then got worse again.

Guarded by unoccupied and unusable forts, protected by live mines, wrapped in miles of rusting barbed wire, trampled on by the feet of many sheep, used as a training ground by regular troops and Home Guard, the Royal Liverpool links remained neglected and uncared for until the summer of 1944, when all fear of invasion having vanished, the Royal Engineers began to clear the mine fields.

This noisy business continued throughout the late summer. Windows rattled, the peace of an August afternoon was rudely shattered by explosion after explosion, each ear-splitting detonation being followed by a plume of dun-coloured smoke from amongst the sand-hills. When no more mines remained, the Engineers retired, leaving the sheep in possession of the mine craters, the barbed wire, the crumbling trenches, and all the hideous mess that had once been a world-famous Championship links.

But as the tide of war turned even further in the Allies’ direction, important work could begin.

The scheme of reconstruction began in the Spring of 1945, priority being given to laying down a compost heap - the stock accumulated in 1939 had long been used up - preparing a new turf nursery, and removing the sheep who by then had fouled the ground, spread weeds over the entire links, and broken down the face of nearly every bunker on the course.

The removal of the wire was accomplished by labour from a local R.A.F. centre, the twisted coils being cut into five-yard lengths, after the supporting posts had been removed, and then dragged by a tractor to a private road where a steam roller crushed them flat so that they could be packed into lorries. In most places the grass had grown so tightly around the base of the coil that it had to be burnt before the tractor could tear the wire from its embedded position.

As work progressed the nature of wartime golfing hazards was revealed.

During the operation, numbers of golf balls were found in what had once been the minefields, an awesome out-of-bounds from which no recovery was possible even in times of acutest rubber shortage.

War clouds proved to have silver linings of sorts as rubble was transformed into features.

The destruction of the concrete forts was recognised to be an expert’s job, so Imperial Chemical Industries were approached and kindly consented to send a demolition squad who literally blew the forts to pieces with much more thoroughness than any enemy action could have accomplished. German prisoners of war had previously dug a deep trench round each fort in which the debris was interred. Sand piled over the broken concrete with a final covering of soil, completed the obliteration of the scars of war and a close planting of marram grass converted the newly-made sand-hills into quite a pleasant feature of the landscape.

The pillboxes that became features no doubt looked like this one still standing in Parkgate

Then it was time to breathe rude health back into the ailing links.

When the sheep, wire and forts had been removed, and trenches and shell holes filled in, the work of restoring the greens and fairways was begun in earnest. Weeds flourished everywhere, mouse-ear chickweed, parsley piert, pearlwort and yarrow being particularly prominent on the greens. An application of sulphate of iron, sulphate of ammonia, and dried blood in equal proportions distributed at a rate of 1½ oz. per square yard worked wonders on the putting surface, a similar treatment being applied to most of the approaches.

Guy Farrah concluded:

Today, after nearly eight years, one can look back on the condition of the links of 1939 without regret, because the damage of war, the effect of unavoidable neglect, the toilsome work of reconstruction are over, and, given reasonable weather conditions, the course should be in first-class order for the Open Championship to be played here at the end of June.

Remarkably, it was, and Northern Irishman Fred Daly emerged as a popular winner of the second postwar Open. Guy Farrar is seated far right.

.jpg)

Advertisement